Learning-code remote control and how to decode it, with program code source Leave a comment

Unfortunately, there are many sources circulating on the internet that have been copied from open-source projects and are now being sold commercially. The code for Code-Learning remotes is one of those cases.

If open-source resources didn’t exist, we probably wouldn’t have witnessed this level of progress in science and technology. Therefore, instead of thinking only about personal profit, it’s far more worthy to think about the **collective benefit and refrain from selling such codes. By releasing them for free, we can all play a real role in raising the overall level of knowledge in the community.

Remote controls have become extremely common these days — from garage door openers to car alarms and lighting controllers, they all follow the same basic principle: wireless transmission of information.

Click to read the article ‘Building a 4-Channel Remote Control‘

There are different mediums for transmitting data. One of the most widespread is infrared (IR), which we’ve all seen in TV and home appliance remotes. The other major category is radio-frequency (RF) remotes, which use radio waves to send data.

Our discussion today is about the second type: RF remote controls.

For these remotes to be able to transmit information, they first need to modulate the data onto a carrier wave. By doing so, the information gains the ability to propagate through the air.

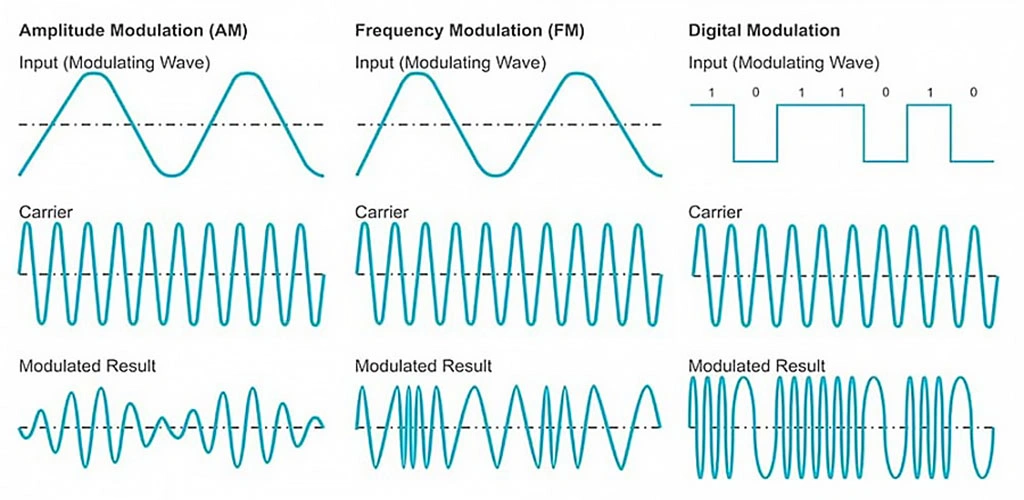

Modulation comes in two main categories: analog and digital, each of which is further divided into several subtypes.

In modulation, the high-frequency carrier signal is altered according to the message signal. The carrier signal has several properties — including amplitude, frequency, and phase — that can be varied based on the message signal. This is exactly what gives rise to the different types of modulation.

(See the image below)

As you can see in the image above:

- In AM (Amplitude Modulation), the data signal affects the amplitude of the carrier wave.

- In FM (Frequency Modulation), the data signal affects the frequency (the “density” or instantaneous frequency) of the carrier.

FM has a much greater range than AM because in AM any reduction in amplitude directly means a reduction in transmitted power.

The next type is digital modulation (Keying), which is actually a special form of FM.

In digital circuits we only deal with logic 0 and 1. These are converted to two different frequencies:

- F0 → represents logic 0

- F1 → represents logic 1

The receiver’s job becomes very simple: it just needs to detect and distinguish between F0 and F1. This type of modulation (or very similar ones) is what most radio remote controls use to transmit data.

Click to read the article ‘What is Remote Hopping?‘

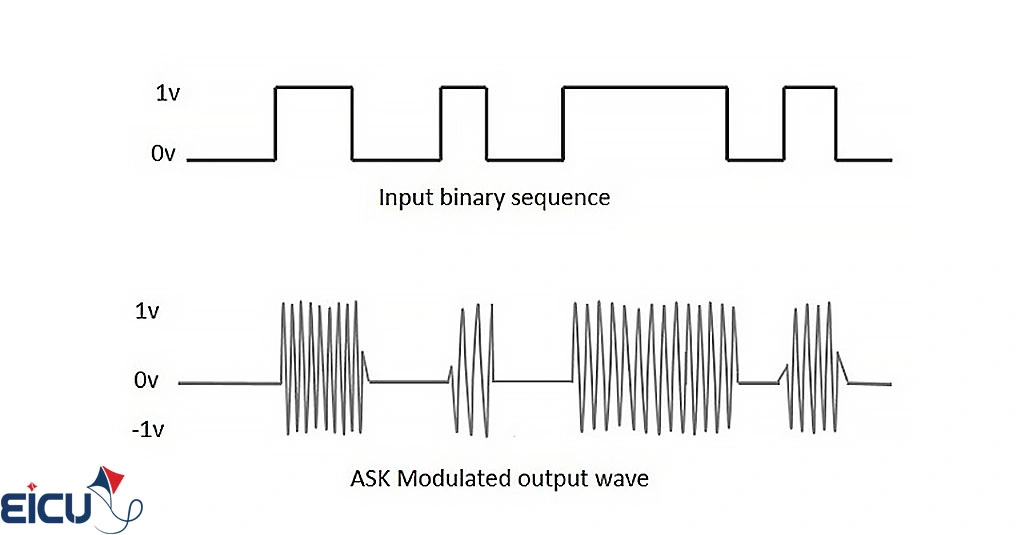

Code-learning remotes specifically use ASK (Amplitude Shift Keying) modulation to send data.

ASK is a simplified version of digital modulation: the F0 frequency is completely removed. Only F1 is used:

- When the data bit is 1 → the transmitter sends the carrier at frequency F1

- When the data bit is 0 → the transmitter turns completely off and no signal is sent at all.

This clever trick greatly simplifies both the transmitter and the receiver:

- The transmitter only needs to generate the carrier at frequency F1 (or turn completely off).

- The receiver only needs to detect the presence or absence of that same F1 frequency.

Types of Remote Receivers

So far we’ve seen how data is transmitted. To build a complete remote-control system, we first need to receive the waves sent by the remote (transmitter), process them, and then perform the action requested by the user.

Since we’re using ASK modulation, we need an ASK receiver that works at exactly the same frequency as the remote. For example, if your remote operates at 433 MHz, the receiver must also be tuned to 433 MHz — otherwise the circuit simply won’t work.

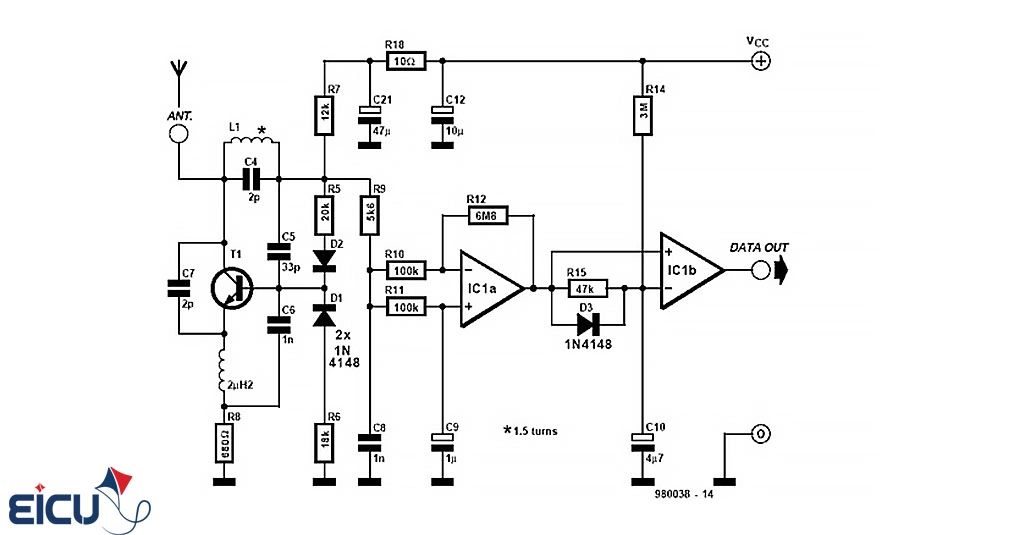

As shown in the picture below, it’s technically possible to build the receiver circuit yourself from discrete components, but because RF design has many subtleties and pitfalls, it is strongly not recommended. It’s far better and much more reliable to use ready-made receiver modules that are widely available on the market.

Remote controls are commonly available in two frequencies: 433 MHz and 315 MHz. When buying a receiver, make sure it exactly matches the frequency of your remote.

In the market right now, you’ll basically find two main types of ASK receivers:

The older (classic) model is a simple super-regenerative receiver built around a few transistors. It has lower sensitivity and accuracy, is very susceptible to environmental noise, but is very cheap. It operates at 5 V and gives a clean digital (0/1) output — however, because of its detection method, it is extremely prone to interference and false triggers from noise.

(See the picture below)

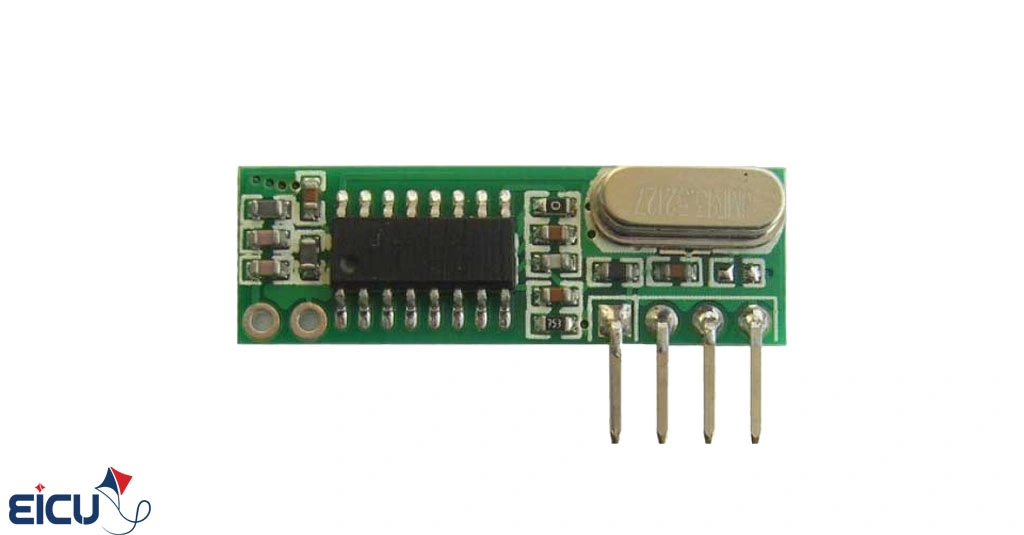

The newer model is a super-heterodyne receiver with a much more sophisticated detection circuit. It uses a quartz crystal for frequency stabilization, which gives it significantly higher reception quality, better sensitivity, and much greater accuracy and immunity to noise compared to the older super-regenerative type.

These receivers can operate perfectly with both 5 V and 3.3 V, and they also provide a clean digital data output. In fact, the pin layout of both the old and new types is designed to be pin-compatible, so you can easily swap one for the other. If you’re not satisfied with the range or performance of your current receiver, simply replace the old super-regenerative module with a super-heterodyne one and you’ll immediately notice a significant improvement in range and reliability.

Code-Learning Remote Protocol

Now that we’ve successfully received the signal, the next step is to understand the communication protocol used by code-learning remotes so we can decode it properly.

The first thing that usually confuses people is the term “code-learning” itself.

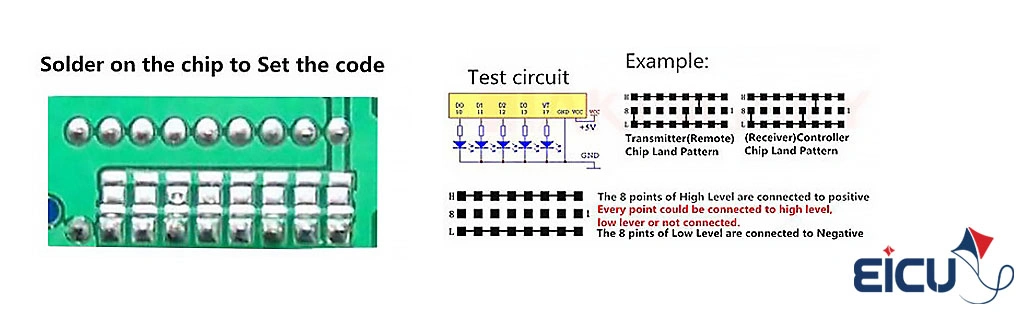

Before code-learning remotes became widespread, there were fixed-code remotes. These older fixed-code remotes had 8 DIP switches (or solder pads). To program them, you had to manually set each switch to either 0 or 1 — and you had to set the exact same pattern on both the transmitter and the receiver for them to recognize each other. This manual process was called “coding or code setting.

The reason they’re called fixed-code remotes is that the receiver stores a permanent, unchanging code. If you want to add another remote to the same receiver, you have to program it with exactly the same code as the others use. From a security standpoint, this is a big problem: once someone discovers your 8-bit (or 10-bit) code, they can easily make a duplicate remote and open your gate or disarm your alarm.

Code-learning remotes, on the other hand, offer much higher security. Each remote is pre-programmed at the factory with a unique, random 20-bit (or longer) identification code. No two remotes in the world have the same code.

Therefore, for the receiver to accept a remote, it must learn and store that remote’s unique code in its memory. Later, whenever a button is pressed, the receiver checks whether the transmitted code matches one of the stored (learned) codes. This process is called “learning” — hence the name code-learning remotes.

Fortunately, the protocol used in almost all code-learning remotes is essentially the same, regardless of whether the transmitter IC is HS1527, EV1527, or any other member of the same family. They all use OTP (One-Time Programmable) encoders and follow the same transmission format.

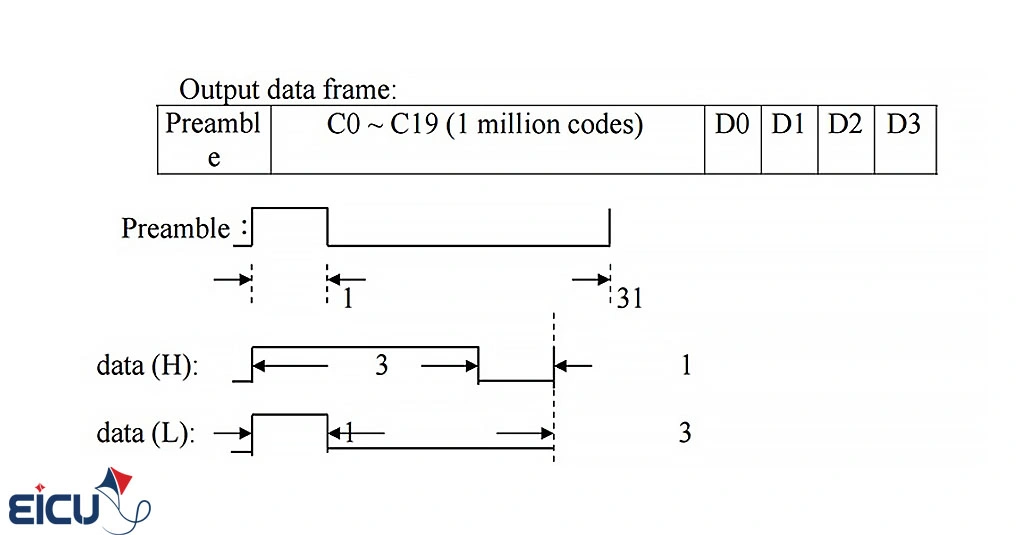

In this method, 24 bits of data are transmitted from the remote: the first 20 bits are the unique identification code for each remote, and the last 4 bits indicate the status of the pressed buttons on the remote.

At the beginning of every transmission, a synchronization signal (Preamble) is sent first. Once we receive this preamble, we must wait to receive the subsequent 24 bits of valid data.

Based on the explanations provided, we need three distinct states: the first for generating the synchronization signal (Preamble), the second for representing logic 1, and the third for logic 0.

- Synchronization state: In this state, if the high (1) signal duration is, for example, 1 microsecond, the low (0) duration must be 31 microseconds.

- Logic 1 state: In this state, if the high (1) signal duration is, for example, 3 microseconds, the low (0) duration must be 1 microsecond.

- Logic 0 state: In this state, if the high (1) signal duration is, for example, 1 microsecond, the low (0) duration must be 3 microseconds.

Note that the times mentioned are just examples. To clarify, the actual durations are determined by the internal oscillator of the IC, but the ratios remain as described.

Program Topology for the Remote

I’ve seen many sample codes for this purpose — both those sold online and those published for educational reasons — and none of them use a proper method. Some examples require that the remote’s oscillator resistor be a specific value (because the code only checks the low duration), have poor range, stop working properly when the remote battery weakens, and cause many other issues.

But now that you’re familiar with how the remote works, it’s time to write a program — using the features and capabilities available in microcontrollers — that can identify the received code and respond accordingly.

To decode the transmitted data in the best possible way, you should do this: Upon detecting a rising edge, start a counter. On the falling edge, read the counter value, reset the counter to zero, and on the next rising edge, compare the previous counter value with the current one — it should match one of the states described above.

Be precise: you must strictly follow the transmission pattern of the remote (first the preamble, then the 24 bits of valid data), because environmental noise can randomly create those states. If you don’t enforce the pattern, your receiver might react unexpectedly and toggle the output on or off randomly (something we’ve seen in some receivers).

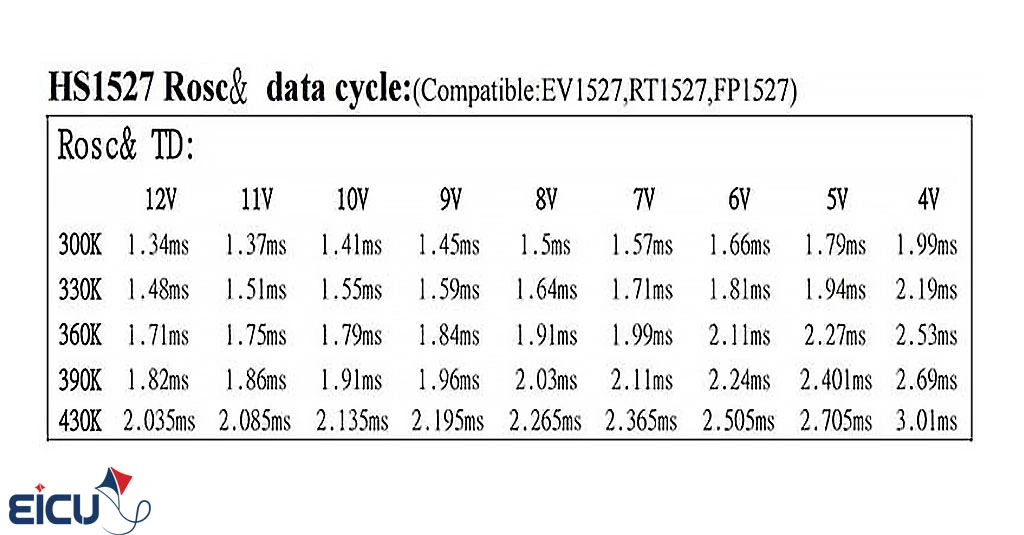

The key question is: at what speed should our timer/counter start counting so we can accurately measure the pulse lengths with sufficient precision? To answer this, we refer to the datasheet of the mentioned IC and encounter the following table:

The table actually shows the total transmission time for one complete data frame at different supply voltages and different resonator resistor values. The shortest possible time for the chip to transmit one frame (24 bits + preamble) is 1.34 ms. Since each frame consists of 128 pulses, the average length of one pulse is approximately 10 microseconds.

Therefore, if we run our timer/counter at 1 MHz (i.e., 1 count = 1 microsecond), we will be able to measure the length of each pulse with excellent accuracy.

Explanation of the Provided Source Code

The source code is available in two versions:

- CodeVision AVR

- GCC (AVR-GCC)

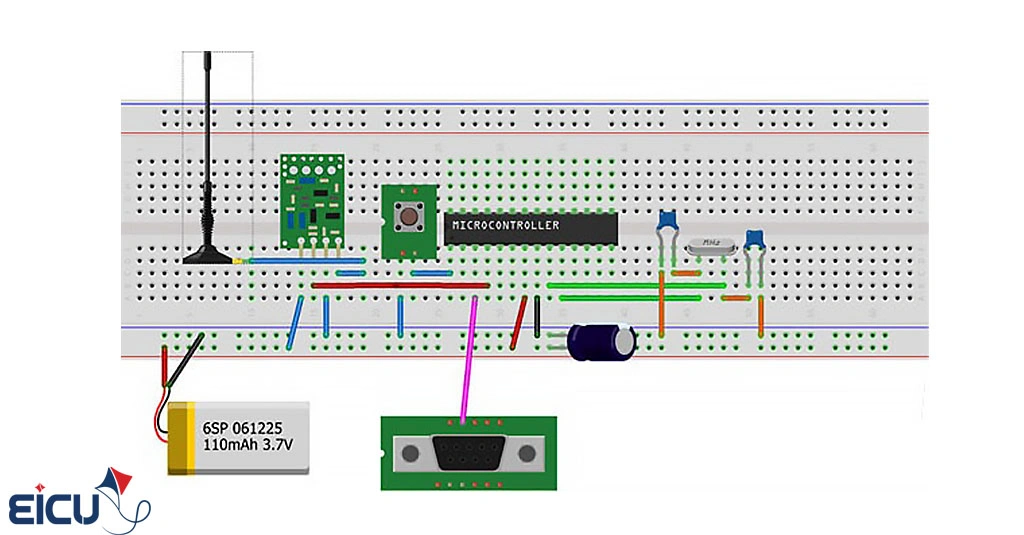

It has been implemented using the ATmega8 microcontroller.

- The data output of the receiver module is connected to pin 4 of the MCU (which is INT0 – external interrupt 0) to detect edges.

- Timer/Counter0 is used to precisely measure the duration of each pulse.

The code is written in a clean, highly portable way so you can easily adapt it to any other microcontroller of your choice.

The microcontroller runs at 8 MHz using an external crystal.

This code has been tested with several real remotes:

- Both 315 MHz and 433 MHz versions

- With a 433 MHz remote and no antenna on the receiver, reliable operation was achieved up to approximately 8 meters!

Download the Remote Control Source Code

For the latest version of the library and full documentation, please refer to the post titled:

“4-Channel Fully Free Remote Control Project with Complete Documentation

FAQ – Learning-code remote control and how to decode it